Nothing in Shakespeare could match the impact of the short speech delivered in the middle of the second act of “You Can’t Take It With You” at the South Compound Theater on the night of January 27, 1945. Making an unscripted entrance, Col. Charles G. Goodrich, the senior American officer, strode center stage and announced, “The Goons have just given us 30 minutes to be at the front gate! Get your stuff together and line up!”

Nothing in Shakespeare could match the impact of the short speech delivered in the middle of the second act of “You Can’t Take It With You” at the South Compound Theater on the night of January 27, 1945. Making an unscripted entrance, Col. Charles G. Goodrich, the senior American officer, strode center stage and announced, “The Goons have just given us 30 minutes to be at the front gate! Get your stuff together and line up!”

At his 4:30 staff meeting in Berlin that very afternoon, Adolf Hitler had issued the order to evacuate Stalag Luft III. He was fearful that the 11,000 Allied airmen in the camp would be liberated by the Russians. Hitler wanted to keep them as hostages. A spearhead of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev’s Southern Army had already pierced to within 20 kilometers of the camp.

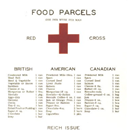

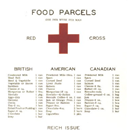

In the barracks following Colonel Goodrich’s dramatic announcement, there was a frenzy of preparation — of improvised packsacks being loaded with essentials, distribution of stashed food, and of putting on layers of clothing against the Silesian winter.

As the men lined up outside their blocks, snow covered the ground six inches deep and was still falling. Guards with sentinel dogs herded them through the main gate. Outside the wire, Kriegies waited and were counted, and waited again for two hours as the icy winds penetrated their multilayered clothes and froze stiff the shoes on their feet. Finally, the South Camp moved out about midnight.

Out front, the 2,000 men of the South Camp were pushed to their limits, and beyond, to clear the road for the 8,000 behind them. Hour after hour, they plodded through the blackness of night, a blizzard swirling around them, winds driving near-zero temperatures.

At 2:00 a.m. on January 29, they stumbled into Muskau and found shelter on the floor of a tile factory. They stayed there for 30 hours before making the 15.5-mile march to Spremberg, where they were jammed into boxcars recently used for livestock. With 50 to 60 men in a car designed to hold 40, the only way one could sit was in a line with others, toboggan-fashion, or else half stood while the other half sat. It was a 3-day ordeal, locked in a moving cell becoming increasingly fetid with the stench of vomit and excrement. The only ventilation in the cars came from the cracks between the wall planks. The train lumbered through a frozen countryside and bombed-out cities.

Along the way, Colonel Goodrich passed the word authorizing escape attempts. In all, some 32 men felt in good enough condition to make the try. In 36 hours, all had been recaptured.

The boxcar doors were finally opened at Moosburg and the Kriegies from the South and Center Compounds were marched into Stalag VIIA.