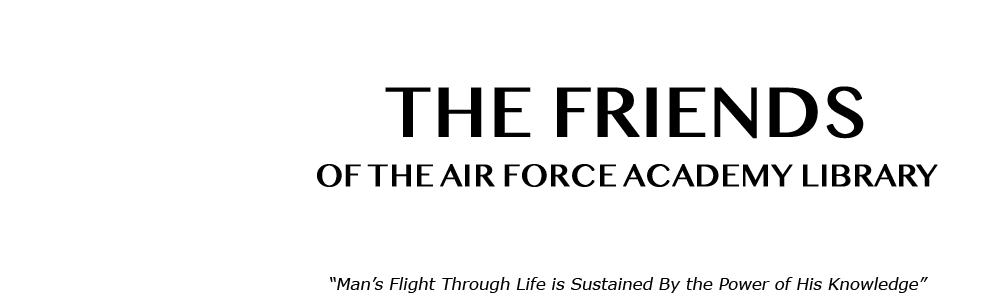

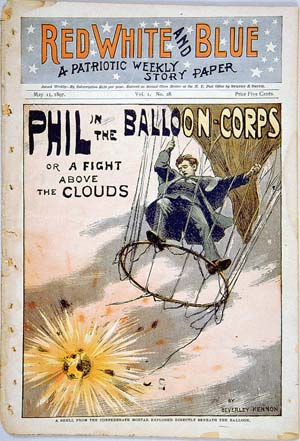

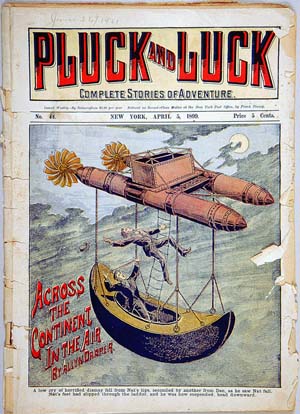

Dime Novels

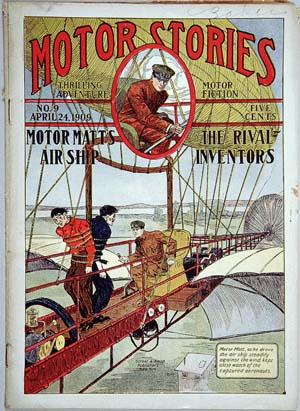

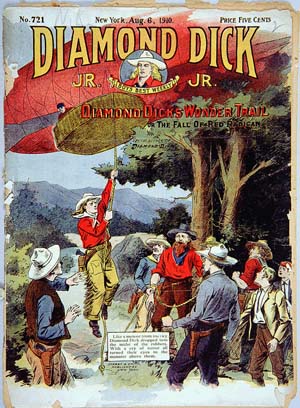

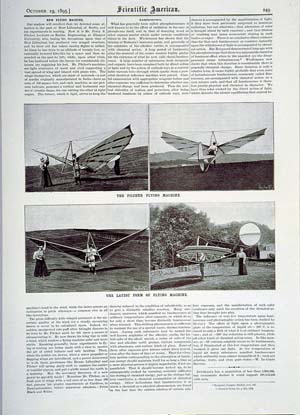

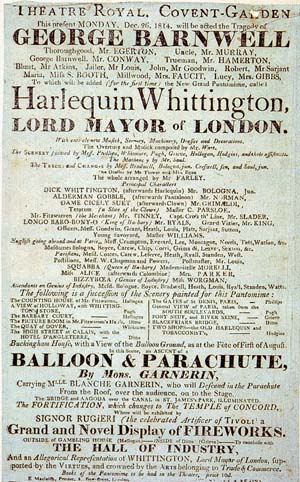

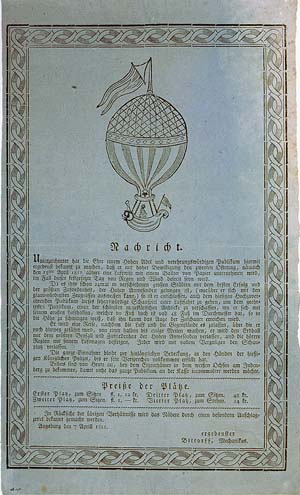

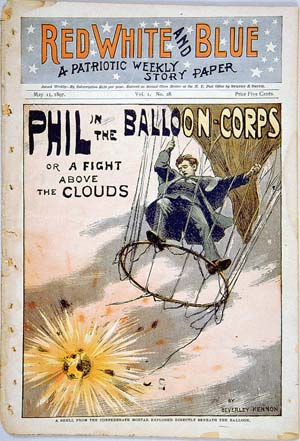

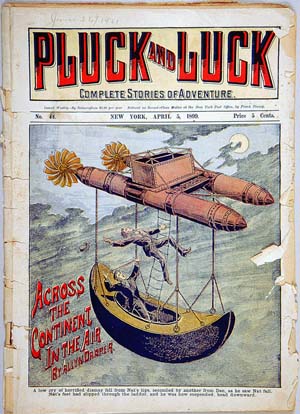

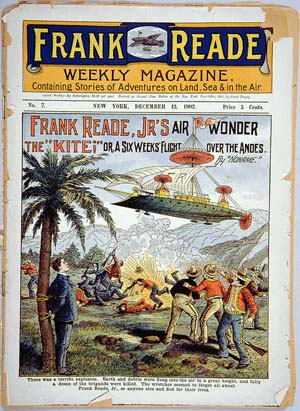

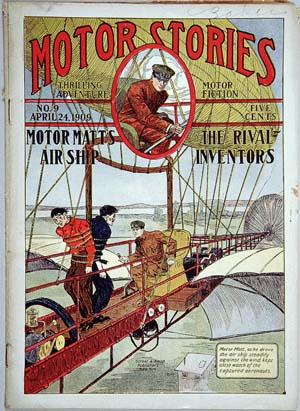

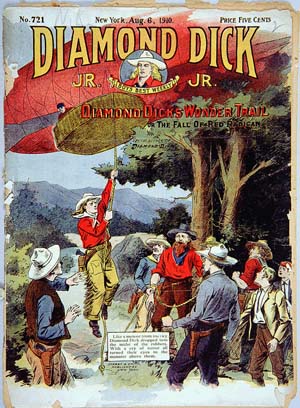

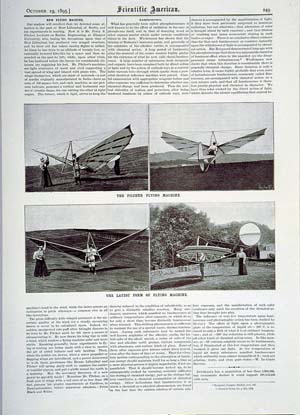

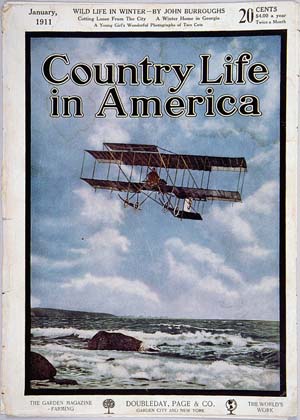

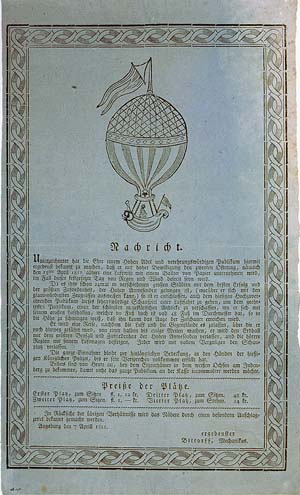

“The dime novel,” as Russel Nye has observed, sprouted in the eighteen-forties and fifties, flowered in the sixties and seventies, and drooped and died at the turn of the century.” Nevertheless, this form of popular fiction had a strong attraction for young men during the half-century of its popularity. Although many stories were Westerns, others, Nye points out, “covered the Revolution, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Civil War; they used pirate stories, sea stories, city stories of high and low life, crime stories, bandit stories, stories of exploration, adventure, history, love, romance.” The writing was formulaic and the characters often coarse, but the stories stressed virtuous behavior. As time went on, however, the emphasis turned to “sensationalism, violence, and overwrought emotionalism.” Some stories included balloons, airships, and imaginative flying machines as drama-heightening devices, and the colorful cover art focused on these situations. It is quite possible that the adventures of dime-novel heroes like Frank Reade, Jr., motivated the first generation of pilots. The situations in these stories presaged the use of aviation in films, pulp novels, and radio serials. The editions presented were published between 1897 and 1910.